Building a better bus system for the Bull City

How we incorporate lessons from New York’s bus service

Introduction

Earlier this week, Democratic candidate Zohran Mandani secured a decisive victory in the New York City mayoral election. A democratic socialist and current state assemblyman, Mayor-elect Mamdani’s campaign has focused on building a more affordable city— freezing the rent, operating municipal grocery stores, and providing fast and free bus service for all New Yorkers.

Mayor-elect Mamdani made fast and free buses a flashpoint for his affordability-focused campaign

The bus has become central to redistributive policy discourse, with fare-free service considered an attainable (albeit ambitious) goal for many transit authorities. For one, bus ridership in cities across the country is overwhelmingly low-income— in Durham, the figure is 88%. The reasoning goes that eliminating fare collection on buses benefits the disproportionately low-income ridership. Riders also spend less time stopped for fare collection, and experience fewer altercations with the operator or between other riders, providing a faster and safer ride.

Durham is one of the largest bus systems in the country to operate fare-free network-wide, having suspended fare collection during the COVID-19 pandemic. Other mid-sized cities have had varying levels of success with fare elimination— Richmond, VA has seen substantial transit ridership increase and plans to expand its Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) service, while funding and safety concerns in Kansas City have led the system to reinstate fares there. However, eliminating fares is a major political hurdle and begs the question: what good is free bus service if the bus doesn’t take you where you need to go, when you need to go, and in a timely manner?

For the bus to truly be a redistributive public service, it must accomplish these other goals— to be relevant, fast, and frequent. Durham’s current local and regional bus service suffices these requirements in small pockets of the city, predominantly downtown where the vast majority of bus ridership can't afford to live. So, here’s a GoDurham and GoTriangle rider’s take on how to build a better bus system for the Bull City.

A relevant bus

The GoDurham bus system currently operates 12 routes, all of which start and end at the downtown Durham bus station. The City has acknowledged that this hub and spoke system is inconvenient for crosstown riders and is launching routes that would accommodate those riders and bypass the downtown station. One other opportunity to reduce the number of transfers needed is to through-run routes so less riders require transfers. For example, a route running from Duke University Hospital to East Durham would enable riders to ride directly there, with the option to transfer elsewhere via the downtown station.

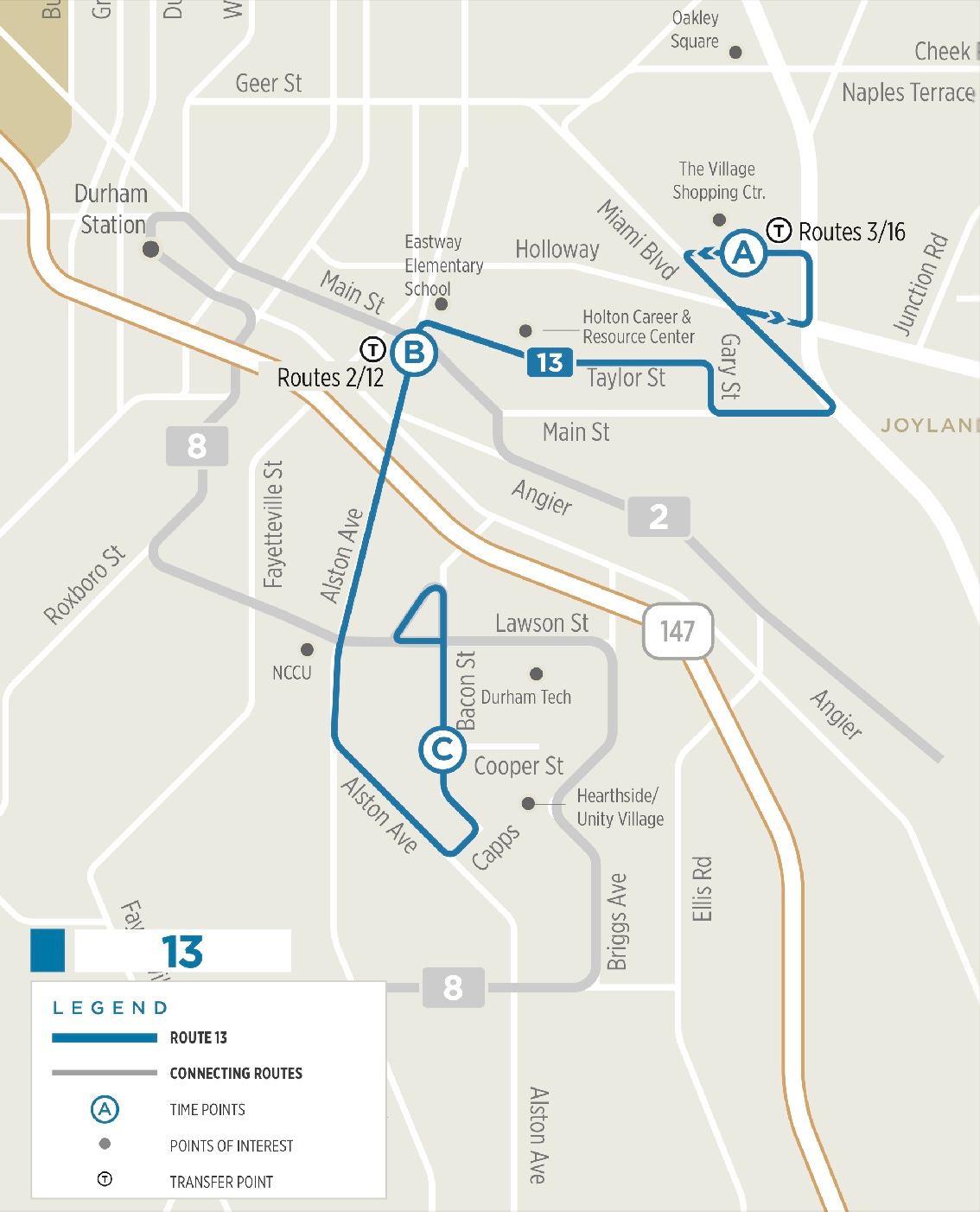

GoDurham’s Route 13 marks the system’s first crosstown service, with additional routes set to begin service in the years to come

A fast bus

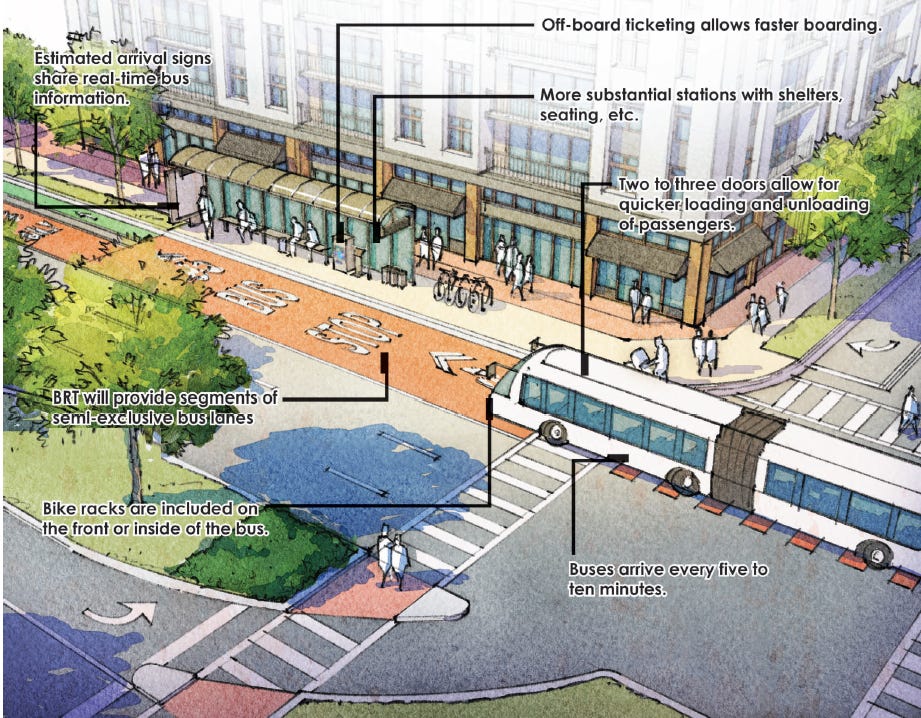

Eliminating onboard fare collection only marginally improves on-time performance for bus routes. Fast buses need a series of intrastructure improvements. For example, bus pullouts at stops along most routes reduce vehicle traffic buildup. Bus-only lanes with platform boarding and traffic signal priority along high-frequency corridors maintain speedy service. Even placing bus stops just past traffic signals improves on-time performance. Durham’s recently-released Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) service concept incorporates many of these infrastructure improvements.

A visual concept of Durham’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line

A frequent bus

The changes listed above only serves riders so much until it takes the secret sauce to boost service to a level that rivals private vehicle ownership— frequency.

Buses arriving every 15 minutes ought to be a standard. For peak service, buses arriving every 12 minutes mimics substantially higher frequency- should a rider miss their bus, they likely have to wait at their stop or the station for less than ten minutes. This is a game-changer from the current service, where many riders wait for half-an-hour for their first, second, on even third bus to arrive.

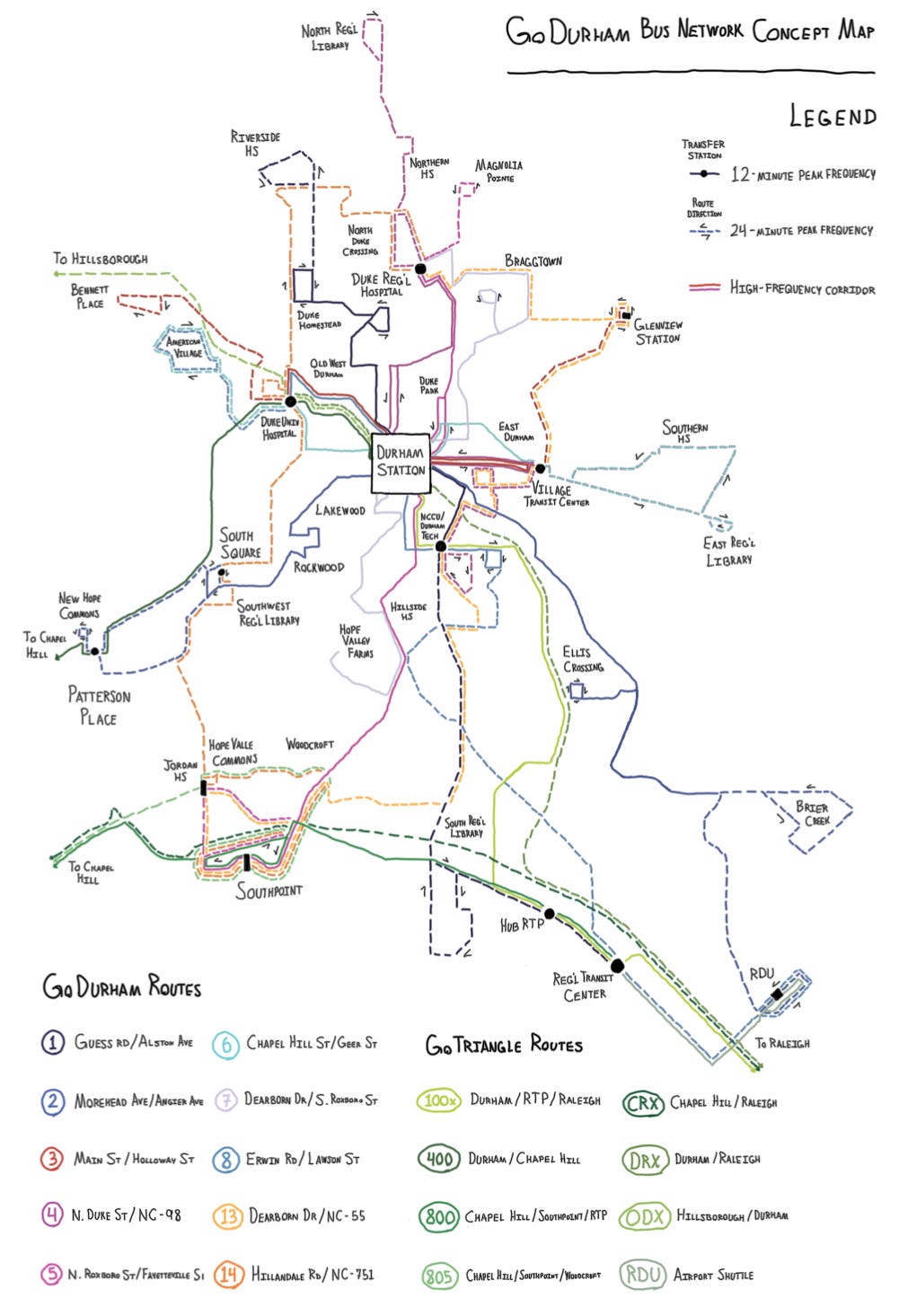

I’ve included below a concept map a what a GoDurham system incorporating these changes might look like. I based this concept on the Short Range Transit Plan set by the City.

Conclusion

Better bus service for Durham residents is not a luxury. Buses that run where riders need to go, faster, and more frequently can expand economic opportunity in communities where it’s needed most. It can save Durham residents valuable time whether they drive downtown to work daily or take three buses a day to reach two jobs on opposite sides of town.

The bus, at its highest capacity, can reduce congestion on our city’s streets and highways and keep Durham moving.

Great post! We definitely need major changes to the built environment to make transit better and create a truly walkable and transit-friendly city. I am proud of being fare-free and hope to continue that policy.

Nice! I really like the route changes you've suggested. I live in Rockwood and the current 10B route through Lakewood makes it super inefficient to get anywhere, but your suggestion is a huge improvement connecting several of the cities transit opportunity areas across all income levels.

I really struggle with what the right thing to do is regarding fare-free transit. I love that Durham continues to vote for it, but all it would take right now is one vote against it to cripple our system's current ridership. It also results in common issue where routes and ridership prioritize mostly low-income riders (which is great) but sometimes at the cost of routes through high-density areas and perceived 'safety' from middle and high income riders, who we need to care about and fund more transit improvements. I wonder if there's a middle ground where fare-free passes are easy to obtain for low-income riders, but we have a fare for everyone else with an easy tap-to-pay system to help subsidize the system.