Your city (or state) is not full

Remedying the housing affordability crisis and vehicle congestion in your town

One of the most common sentiments I observe on social media posts having anything to do with cities, particularly within the context of moving, is one of rejection: no thanks, we’re full.

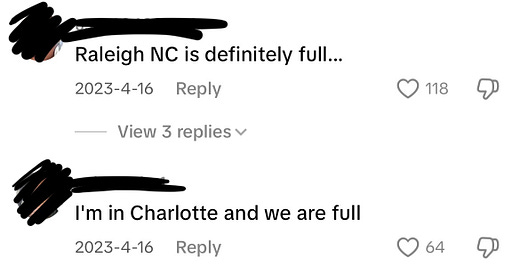

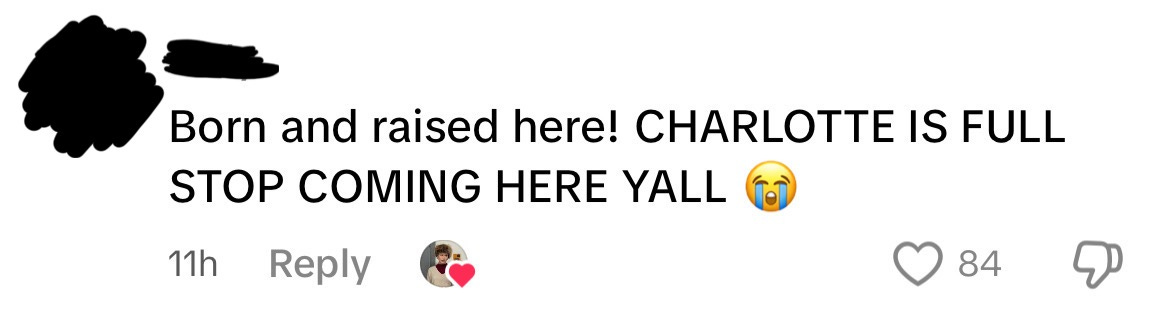

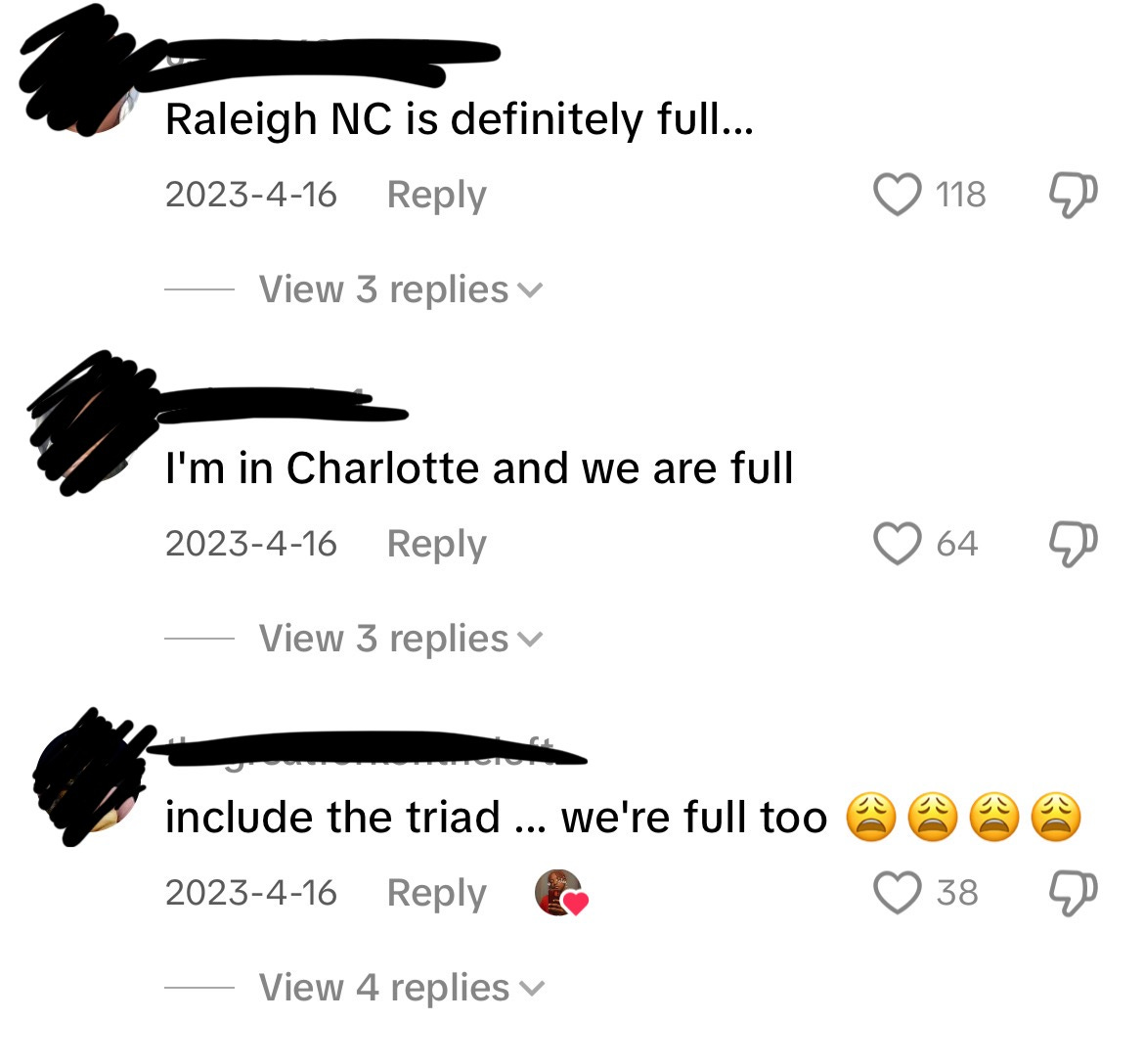

I see it from people from all over the state:

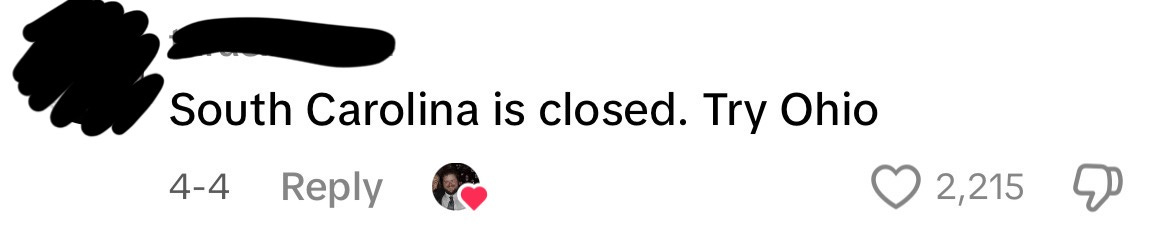

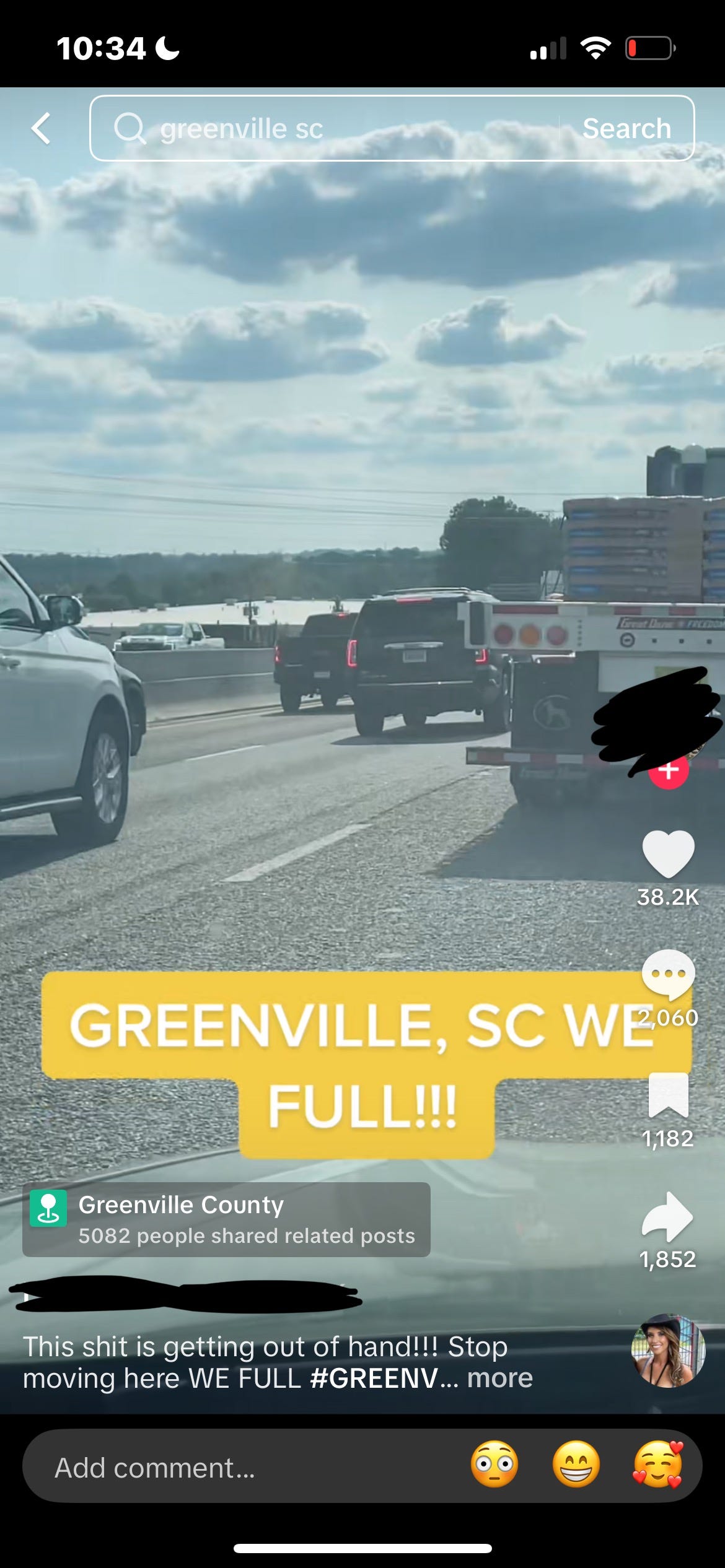

… and those from South Carolina as well:

But in what context are these cities and states full?

It is often in the context of cars. There is too much congestion, too little available parking for longtime residents who have become accustomed to a certain standard of efficiency when driving around town.

This is a perfectly valid reaction to such a conundrum. It’s arguably more understandable in the context of housing, where much of the housing being built in the community is designed for those moving from afar with increased spending power. It’s a necessary reaction in the context of a community, particularly one that has been historically marginalized, being displaced in the name of ‘progress’ or ‘renewal’ for the aforementioned newcomers.

However, there are plenty of contexts where it’s an ill-informed conclusion. Who is saying it, where they’re referring to, and what they want done about it all influence that outcome. It’s also important for us to consider that wealthier residents reap the benefits of the same population influx they may bemoan; new amenities and expanded economic opportunities they can directly utilize.

Regardless of status or other factors, this population will generally skew towards the ‘we’re full’ response. But is that entirely true?

These are the population densities, measuring how ‘full’ a city is, for the densest cities in the United States:

New York, NY: 29k/sq mi

San Francisco, CA: 19k/sq mi

Boston, MA: 14k/sq mi

Chicago, IL: 12k/sq mi

Philadelphia, PA: 12k/sq mi

Conversely, these are the population densities for the principal cities of the largest growing metropolitan areas in the country:

Austin, TX: 3k/sq mi

Raleigh, NC: 3k/sq mi

Orlando, FL: 3k/sq mi

Jacksonville, FL: 1k/sq mi

Dallas, TX: 4k/sq mi

Houston, TX: 4k/sq mi

Charlotte, NC: 3k/sq mi

San Antonio, TX: 3k/sq mi

The difference in population density between these two groups of cities is dramatic. On the surface, the conclusion may be that these lower-density cities offer a better quality of life than the crammed major cities across the country. However, this sprawl is expensive for municipalities to maintain. Because residents pay lower taxes on sprawling properties with lower tax values, municipalities have even fewer funds to maintain more road surface. When it all shakes out, tax dollars from residents of these sprawling, low-density cities are inefficiently used and could be going much further to actually improve quality of life: sidewalks, bus stops, better schools, better parks, and more amenities.

Many of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas in the country are developing in a way that only places an added strain on these resources. Here’s some the most pressing issues facing low-density cities:

Housing

The characterizing feature of low-density cities and their surrounding communities is the single-family house, which has become the pinnacle of the American Dream. However, it’s become rapidly unachievable for many because of just how expensive it is to build. Single-family homes cost more to construct than their denser counterparts and require more sprawling infrastructure to build and maintain. Sprawl leads to higher obesity rates, traffic fatalities, emergency response times, and infrastructure costs, all of which are shouldered by the municipality and ultimately residents.

Despite these negative externalities, a majority of Americans— 57%— prefer sprawling communities where they have to drive to their destination over denser neighborhoods where more amenities are within walking/biking/transit-accessible distances. That still leaves over 40% of Americans who prefer walkable neighborhoods and cities, many of which are priced out of the few truly car-independent cities in the country. Because they’re so few and far between, there’s a profound market balance indicating that there’s much higher demand for density than there is sprawl.

Transportation

The more sprawl there is in our metropolitan areas, the more residents must rely on a personal vehicle to get around. These cities prioritize the most individualistic and most dangerous mode of transport. The fact that each person is driving their own vehicle increases instances of human vehicle error, leading to more delays, injuries, fatalities. Active and sustainable transportation alternatives alleviate existing infrastructure, but only when destinations are within walking/biking/transit-accessible distances.

Land use

This level of demand for personal vehicles requires significant space dedicated to cars— highways, driveways, parking lots, garages, and more. These spaces have two things in common: they take away space that would otherwise be used by people and they generate little to no tax revenue for municipalities. In fact, they cost far more for the taxpayers for municipalities to maintain. Reducing reliance on parking and other car-dependent infrastructure opens new opportunities for local governments and residents alike.

Municipalities can generate more tax revenue from denser development, less of which has to go towards endless road construction and maintenance. The added residents from this development isn’t as much of a strain on the municipality or the community because their added tax dollars outweigh their burden on community resources (e.g., competition in the housing market, vehicle traffic on major roads).

So no, your city is not full if our cities can reverse their direction on housing availability, transportation choices, and land use practices.

Well said! It’s sad that so few people understand the dynamics at play that produce unaffordable housing and congested highways. It leads to well-intentioned people pointing fingers in all the wrong directions, like increased density.

Before I moved to Europe for more walkability, I lived in Durham, NC, one of the those fast-growing regions (coupled with Raleigh) that you mentioned in this piece. Everyone in my neighborhood was angry whenever a new apartment building went up downtown, thinking that was the source of gentrification, even though those buildings actually housed people who would have otherwise gentrified the lower-income areas just outside of the city center. It’s sad because I loved Durham. It could have been an amazing city with the density and walk ability it deserves. I didn’t want to waste more of my life wishing for the lifestyle I craved though so I left.